|

| |

| |

South Africa We often saw housing developments of modest block houses on tiny lots. The houses often had identical solar hot-water systems on their roofs. These are houses built by the government for poor black and colored workers, and they are scattered all over. They suggest at least a nominal effort to solve the huge housing crisis. But then, almost as soon as these housing developments are built, desperately poor, unskilled people arrive from the countryside, and even from other countries, hoping to share in a better life. They throw up warrens of shacks called "informal housing" by whites. (Talk about euphemisms!) The hopelessness of these instant slums overwhelms the decent housing being provided. In the heading photo above, notice a satellite dish sprouting from the roof of a shack. It seems impossible that a family living in these conditions could afford the very high prices for satellite service. We asked some people about it. The consensus was either that it belongs to a shebeen -- a small, unlicensed bar -- or it is just for show. If just for show, that in itself is a sad commentary on the impact of Western affluence and media on people's aspirations.

As Americans, we rightly feel that if perhaps 20% of people in our wealthy county are living in poverty, our system is in trouble. Just imagine if the proportions were reversed. Imagine a country where perhaps 20% of people were comfortable or wealthy, and 80% lived in extreme poverty! That's South Africa. Worlds Apart Despite the fact that apartheid has ended -- and even most whites we met say good riddance -- people in South Africa seem to live in separate worlds. There are 11 official languages: Zulu, Xhosa, Afrikaans, English, Sotho, Tswana, and more that we can't remember. Linguistic and cultural barriers, combined with race and reinforced by huge economic disparities, tend to keep these various groups apart. As whites coming to South Africa, we were struck by the sheer size of its white community. Zimbabwe was very different when we worked there 30 years ago. There, it was always evident that whites were a tiny minority; we lived and worked primarily with blacks. In South Africa, whites are also a minority, but in some areas they are numerous enough to comprise large neighborhoods where one will hardly interact with a black from one day to the next, except for laborers, shop clerks, and servants. In certain areas of Cape Town and probably in Jo'burg also, there are mixed neighborhoods. In predominantly white suburbs, there may now be an occasional family of prosperous Africans. It's a start. Also, students in South African schools are now supposed to study three languages -- Afrikaans, English, and the African language of the region -- though we don't know how often this really happens. Despite these modest changes, South Africa's racial and cultural "worlds" still seem largely separate. Whites, for example, seem to stick together and have little social contact with blacks. We want to emphasize that the South African whites we met were extraordinarily kind, helpful and friendly people -- from those in whose homes we stayed, to the man who stopped his car to invite us for coffee, to the innkeeper who put us up for free, to the countless number of people who asked about our trip and wished us well. However, few of those we got to know seemed comfortable or optimistic about the "new" South Africa. Fear White South Africans seem more anxious about crime than any other

people we've encountered, anywhere. The homes of whites in the

suburbs are wrapped in security: walls and fences topped with metal

points or razor wire, electric fences, multiple

locks, and alarm systems of all sorts. Signs saying "armed response"

are everywhere -- if an alarm is tripped, armed security

guards will come, Whites were forever telling us to be careful, to stay clear of certain areas -- not only certain neighborhoods, but entire swathes of the country. It wasn't said out loud, not to us anyway, but it was blacks about whom we were being warned. This is so even though many whites fully realize that the overwhelming majority of blacks are kindly, law-abiding people who are most often the victims of crime, not the perpetrators. One white couple recalled that they were young students during the late days of apartheid. They remember apartheid government propaganda, constantly warning them about terrorists, keeping them in a state of fear. In school there were drills in which they practiced hiding under their desks to escape terrorist bombs. No wonder many in the white community feared a bloodbath if blacks ever gained control. Nothing like that has happened. That's not to say it never could. The media in South Africa inflame anxiety about crime. Even fairly responsible

newspapers regularly display screaming headlines about the latest rape

or murder. The crime rate is indeed high in South Africa, but surely

there is other news -- even good news from time to time -- but you

wouldn't know it from the media. On the other hand, the South African

media do not give much coverage to the murders of white farmers. We

eventually learned that white farmers, especially in remote northern

provinces, have been killed by the hundreds, possibly several thousand,

without much publicity. Several responsible people told us that if the true number

of these murders were widely known abroad, the huge investments being

made in South Africa might dry up. As it is, the number of white-run

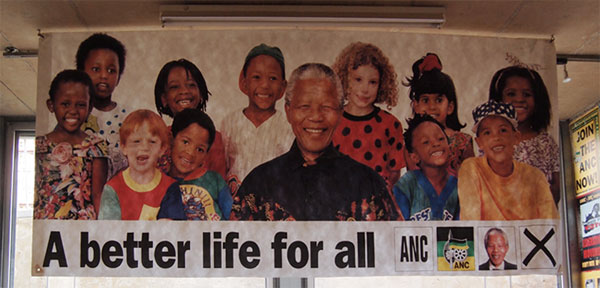

commercial farms is steadily decreasing. The Future We imagine that when Nelson Mandela became the new South Africa's first president, there was a burst of optimism in all of South Africa's worlds -- including the white world. Having feared the worst, white South Africans were heartened when Mandela sought not revenge but reconciliation. Mandela insisted that South Africa be a welcoming home to all who lived in it, whatever their race or language. (We were amazed and touched by the warm admiration that even whites express for Mandela. We ourselves feel that Martin Luther King Jr. was a great man, but we've not heard him praised as consistently and sincerely in the U.S. as Mandela is praised in South Africa.) Another reason for optimism in the early years after apartheid ended was the new constitution. It was, and is, one of the most progressive in the world.

Now, however, almost 20 years have gone by since those heady times, and among some South Africans, fear of the future is building again. One reason is that South Africa's current leaders don't seem to share Mandela's integrity and his commitment to multi-racialism and economic justice. More and more instances of corruption are coming to light. Government needs to be effective in encouraging economic growth and job creation. If that doesn't happen -- if leaders are more concerned with lining their own pockets and those of friends and family -- then the situation could eventually become explosive. Fear about the competence and integrity of the government is felt not only by whites. Recently a widely respected Xhosa woman in the anti-apartheid movement, Dr. Mamphela Ramphele, announced formation of a new political party to oppose the ANC. Another, longer established party, the Democratic Alliance, has some white leadership but growing African support. It already controls Western Cape province and is making inroads elsewhere. Zimbabwe's story is often taken as a warning for South Africa. Things didn't get truly dreadful in Zimbabwe until ordinary Africans began to turn against Mugabe for his failure to achieve land reform and provide a better standard of living for the poor. When Mugabe began to lose support, he played the race card, blaming whites and the west for his people's troubles. That's when things really started to get ugly. Looking a little further into the past, we believe there was an important difference between South Africa under apartheid and old Rhodesia. In Rhodesia, the separation of races and exploitation of blacks were deplorable, but they never reached the bizarre extremes of South African racial policy. Apartheid in South Africa may have done greater, longer-lasting damage to the souls of whites as well as blacks. If developments occur in South Africa parallel to those in Zimbabwe's recent past, the trouble could be far more violent and destructive than it ever was in Zimbabwe. So we watched for hopeful signs when we were in South Africa. One was the growth of a black middle class. We've been told that there are already more middle class blacks than whites in the country. It seems to us that the fear and, often, disdain with which many whites regard blacks will only be overcome when they get to know one another, not as "baas" and employee or servant, but as friends. Not many years ago this would have seemed impossible, but we have occasionally seen blacks and whites socializing, always younger people and students who do not remember the horrors of apartheid and the struggle to be rid of it.

Zimbabwe When we taught in Zimbabwe from 1982 to 1985, it was a relatively prosperous country and a beautiful one. Mugabe had been elected for the first time and things seemed to be going well. Later, back home in the U.S., steadily worsening news from Zimbabwe led us to think that if we ever returned, we'd be depressed and disappointed by the state of the country.

Examples:

The first white family we met in Zimbabwe were respectful and friendly to Africans and genuinely optimistic about their country -- quite a change from south of the border. OK, things are very tough in Zimbabwe. Because the government is corrupt and often incompetent, there is no effective transfer of food, water, or wealth from more fortunate areas of the country to areas that suffer from extreme poverty and drought -- like Berejena, where Zienzele works. Therefore we expect that even as the economy recovers -- which we hope is happening -- less fortunate areas will get little help, and conditions for many people will remain terrible. Still, before actually returning to Zimbabwe, we were beginning to feel

something akin to "donor fatigue." That is, helping people in a

situation that is utterly hopeless can eventually feel like pouring

energy and money down a bottomless well of misery. The happy surprise

was that we didn't feel like that at all when we finally arrived in

Zimbabwe. Life was terribly difficult, to be sure, but people were not

discouraged. At least the possibility of progress was in the air. We

felt that if Zimbabwe ever gets a more competent, compassionate

government, better days will follow.

|

| Start Cape Winelands-Karoo Garden Route Addo Eastern Cape Mpumalanga Kruger Zimbabwe Afterword |